Deep dive into Abercrombie & Fitch ($ANF)

The (Controversial) Phoenix of Retail

1.0 Introduction

Abercrombie & Fitch ANF 0.00%↑ teaches valuable business and marketing lessons, and I’d argue it should be studied in universities. It is also a mirror reflecting the shifting tides of American culture.

Let’s start from the very beginning.

2.0 Its (rollercoaster of a) history

I named it the phoenix of retail, as it has faced near-collapse multiple times, only to rise stronger each time.

2.1 The Humble Beginnings & First Near-collapse

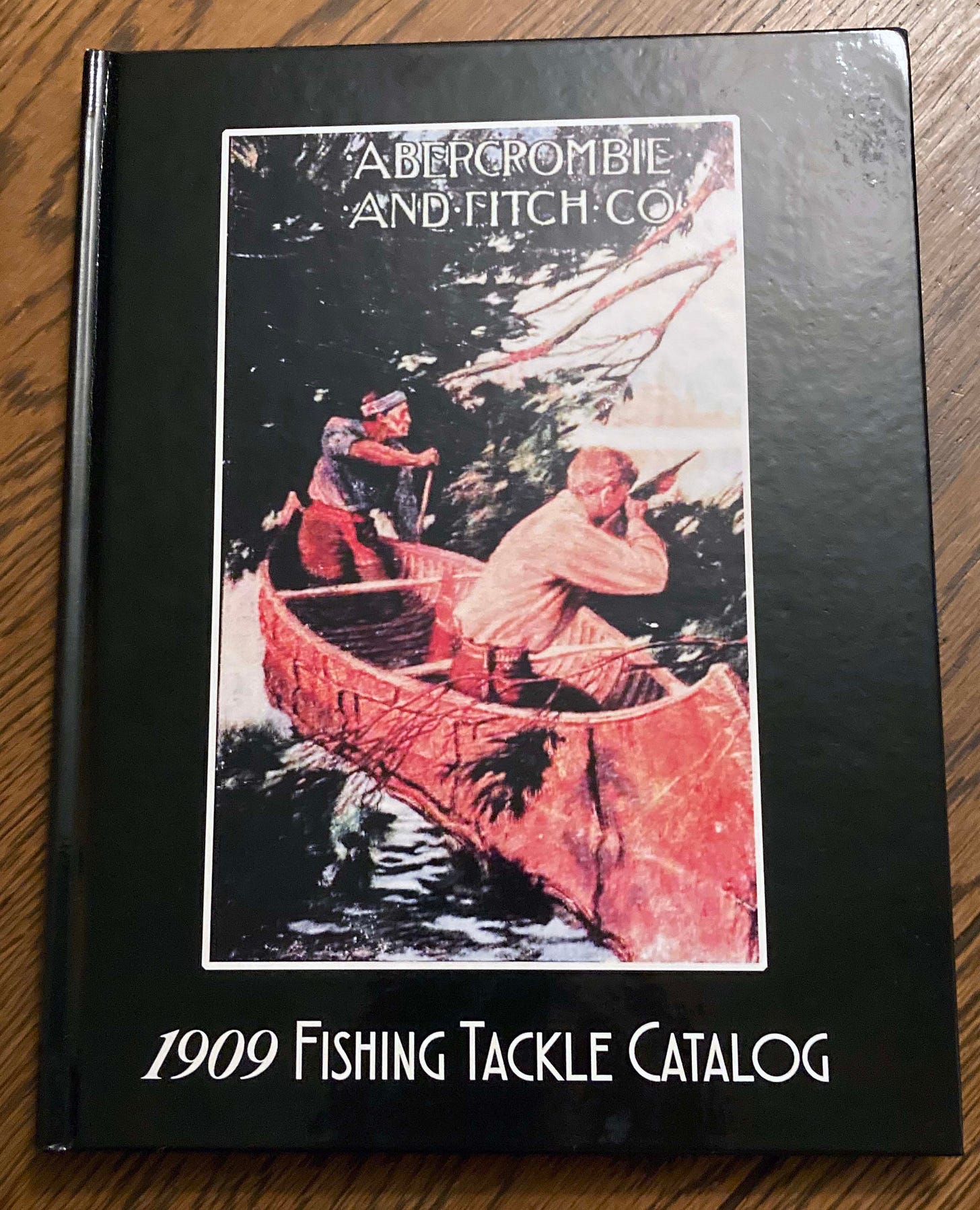

Back in 1892, David T. Abercrombie started his own company Abercrombie Co. specializing in outdoor gear, including fishing rods, tents, and hunting apparel. In 1900, Ezra Fitch, a lawyer and a customer, decided to buy a stake in the company, and in 1904, it was renamed to Abercrombie & Fitch.

However, this partnership only lasted for a few years, as the two of them weren’t getting along, so Abercrombie sold his share in 1907, and that’s where his story ends.

This could’ve been the end of the company.

2.2 The Big Risk That Paid Off

However, Ezra Fitch had plans to grow the company and took a huge risk. He created a 450-page catalog and printed 50,000 copies.

This was a great strategy for raising awareness for the company. Over the following decades, the focus was on expanding the portfolio and appearing to a wider audience, not just the elite outdoorsmen. In the two following decades, the catalog was known as “the most expensive catalog” in the world featuring everything from luxury outerwear to high-end rifles.

It became a brand associated with the elite and attracted celebrity clientele, such as Theodore Roosevelt, Amelia Earhart, and Ernest Hemingway.

In 1928, Ezra was in his 60s, he retired from the business and sold his share of the company.

Since then, for almost 100 years, Abercrombie & Fitch has been around, without any of the founders running (or influencing) the company.

2.3 Post-Fitch Era and Another Near-Collapse

The company’s reputation remained solid, and growth continued. The portfolio kept expanding, and in the 1930s, unique items like portable yachts and safari equipment were added.

During World War II, the company adapted by supplying gear for military personnel, but this shift began to stretch the brand away from its core identity.

The demand for high-cost, niche products wasn’t as high post-war, and its appeal declined. Abercrombie & Fitch failed to connect with the younger, middle-class consumers who were driving retail trends. It became a museum appealing to a shrinking audience of older, wealthier customers. In addition, the rise of discount stores started taking significant market share.

By the 1970s, Abercrombie & Fitch was in deep financial trouble, and in 1977, the company filed for bankruptcy.

However, this wasn’t its end. Oshman’s Sporting Goods, a Texas-based chain, believed that there was value in the brand, so took over Abercrombie & Fitch.

Instead of being a bankrupt company whose story ends in 1977, it got another life.

2.4 The Third Near-Collapse

However, it didn’t go as planned. Oshman’s tried to rebrand the company as a mid-tier retailer, targeting outdoor enthusiasts, rather than the elite. This diluted the brand’s identity further.

Despite all the efforts to reinvent the company, there was no success.

Somehow, it got another chance. In 1988, it was acquired by The Limited, Inc., and in 1992, Mike Jeffries was appointed to lead its transformation.

2.5 The controversial Mike Jeffries era (1992 to 2014)

Over these two decades, the company’s revenue grew from $85 million to $4.5 billion.

Jeffries had a different (and controversial) vision. He wanted to make shopping at the stores an experience. So, he introduced dim lighting, loud music, and the signature scent of Fierce cologne.

Famously, the company did not offer clothing in sizes above L (for women) or above size 10 in women’s pants and above XL for men. This was to accommodate muscular body types, rather than larger body sizes.

Its marketing was provocative, featuring shirtless male models and the campaigns embodied exclusivity and beauty. It was always slim, athletic models reinforcing the idea that Abercrombie’s clothes were only for beautiful people.

The exclusion was intentional. In a controversial interview with Salon in 2006, Mike Jeffries said:

”In every school, there are the cool and popular kids, and then there are the not-so-cool kids. We go after the cool kids. We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends.”

Basically, he was targeting the young generation and the message was “This is what the cool kids wear. If you want to be cool, this is what you have to buy and wear.”

The same was also true of hiring, where if minorities were hired, they had to work in the back, so they were not seen by the public.

In 2000, another brand named Hollister was created, targeting high-school-aged teens, younger than the Abercrombie & Fitch college demographics. It offered lower price points, making it more accessible while still maintaining the “premium” feel. However, there were many similarities, the stores were dark, there was loud music and a signature scent. The employees were referred to as “models” and in 2009, it surpassed the Abercrombie brand in sales.

Its culture extended to the annual report.

Abercrombie & Fitch became a public company in 1996.

The exclusion was one of the reasons behind its growth. However, it brought multiple lawsuits over its discriminatory practices and criticism over its hyper-sexualized advertising and in-store imagery.

Its existing audience was growing older, and the company didn’t keep up with it. By the 2010s, Abercrombie wasn’t seen as much as the cool brand, and consumers gravitated towards brands that felt more inclusive. Mike Jeffries, being a controversial figure, brought on more reputational, legal, and operational challenges, and became a liability to the company.

In 2023, the BBC completed a two-year investigation into several allegations that Jeffries and his cohorts exploited young adult men. He was sued under a civil class action complaint of sex trafficking, estimating over a hundred young models were victimized.

In 2024, Jeffries was indicted by federal prosecutors on criminal charges of sex trafficking and interstate prostitution. He was released on a $10 million bail with his house as collateral and must wear a GPS collar.

3.0 Fran Horowitz - The Phoenix Is Here (Again)

Fran Horowitz became the CEO in 2017 and managed to take a barely profitable company, to one with a 14% operating margin.

To be even more impressive, this was done in a period when retail was struggling.

So, what happened? A lot.

She walked into a company with two global brands (Abercrombie & Hollister) in decline. However, when she was in the malls, she noticed that the two brands became one. It was the same product, with a different logo and different price points.

This had to change, either merge the two brands or make them completely different. She opted for the second option.

3.1 Separating the brands

Hollister became a teen-focused brand. Its customers had time to go to the store, making it an experience as well as a social gathering;

Abercrombie became the brand for busy millennials. They use the stores as a quick experience, often picking up stuff they bought online and trying them on before they quickly leave.

The brands and their stores were optimized for the target customers’ ideal experience.

3.2 Change in/of stores

The stores were no longer dimly lit, but instead, were brighter with welcoming interiors. The overpowering scents were also removed. The mannequins show various body types, and the focus is more on experience, rather than on appearance.

Equally important, the number of stores was significantly reduced. In most cases, the location was great, but the size was 3x what they needed.

This decision reduced the rent expense by over $200 million per year.

Despite having fewer stores, the total revenue didn’t decline. The customers were more engaged, and the revenue per store was increasing.

3.3 Improving the products

It was time for the company to grow up with its customers. So:

Instead of focusing on branded products, they got rid of the logo on the majority of the products;

They invested in better quality, better zippers, better buttons, and softer fabrics;

Started offering more sizes, making it more inclusive (including a Curve Love Fit); and

Instead of telling the customers what was cool and what they should wear, they asked what they wanted.

3.4 Changes in marketing

A “Creator Suite” program was introduced, incentivizing customers to post. The new strategy involved partnering with affiliates/influencers to promote their products on social media. People count on and believe their friends and their peers more than they believe what a company is telling them.

There is some data that 9 out of 10 consumers trust influencers over brands.

This shift to digital and going for user-generated content was the way to go. It didn’t end there. As more was happening online, there was a lot more data being captured on the customer’s browsing activity. So, when a discount offer was sent via e-mail, it was more personalized, which increased the likelihood of converting into a sale.

Fran Horowitz deserves all the credit for this turnaround and the market is finally recognizing the value she brings:

4.0 Historical Financial Performance & Valuation

Back in 2022, the company announced the 2025 targets:

They got there in 2023.

The question is, what’s next? Is this growth and margin sustainable?

Probably not. In my opinion, this is a successful turnaround, not a growth story.

A key part of the capital allocation is returning cash to the shareholders via buybacks.

If the excess cash is returned to the shareholders, significant revenue growth should not be expected. However, given the significant price increase, returning cash in the form of dividends and not share buybacks seems like the better choice.

As for the operating margin, it is significantly above the range that the management expected, and in the long run, it will likely revert closer to the 11% that’s sustainable. Part of this is due to the unexpected tailwind, arising from the temporarily lower freight and cotton costs.

Here’s my DCF model:

Based on my input, the fair value of the company is ~$5.9 billion ($~117/share), below today’s share price of $161.

There are two reasons why I am using input that might seem more pessimistic:

The age of Fran Horowitz - She is in her 60s, and despite doing a great job, it is unreasonable to expect her to run the company for decades to come. Whoever comes next brings uncertainty into the equation.

The nature of the business - When it comes to fashion, it keeps evolving. Companies that are relevant today might not be the ones that are relevant in the future.

4.1 The Bull Case

Here’s what a bull case would look like:

Instead of returning cash to the shareholders are today’s price, the excess cash is deployed in growth, opening new highly-profitable stores;

The successor of Fran Horowitz executes as well as she has;

The company’s new products are well received by its customers, and it can adapt quickly when there’s a change in the fashion trends;

In this case, the fair value today would be closer to $200/share.

4.2 The Bear Case

The excess cash is returned back to the shareholders via buybacks, at today’s elevated share price, which would destroy shareholders’ capital;

The successor of Fran Horowitz makes changes that do not benefit the business (and ultimately, the shareholders);

The company’s offering doesn’t change with the change in fashion trends;

In this case, the fair value today would be below $100/share.

If you enjoyed this post, consider sharing it, it helps the newsletter immensely.

Haven't read it yet, but is the conclusion different from “good company, but investing in clothing industry sucks and is too unpredictable “? Just curious.